If Google Were Mayor

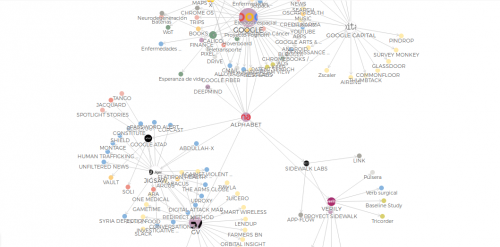

“Quayside,” a 12-acre slice of Toronto waterfront in line to be developed by Sidewalk Labs, the urban-tech-focused subsidiary of Google’s parent company Alphabet. Launched in 2015 by its CEO, Dan Doctoroff, and a number of other Michael Bloomberg affiliates, Sidewalk Labs makes much of its urbanist bona fides. The company is now primarily focused on turning the patch of Toronto-owned land into what it calls the “world’s first neighborhood built from the internet up.”

Quayside would test a novel “outcome-based” zoning code focused on limiting things like pollution and noise rather than specific land uses. If it doesn’t bother the neighbors, one might operate a whiskey distillery in the middle of an apartment complex.

a data-harvesting, wifi-beaming “digital layer” that would underpin each proposed facet of Quayside life. According to Sidewalk Labs, this would provide “a single unified source of information about what is going on” to an astonishing level of detail, as well as a centralized platform for efficiently managing it all.

Those residents might not have a choice in how much privacy they give up to call Quayside home, even if they don’t like the terms of use. The same could be said for anyone who uses its public spaces.