How to connect Thunderbird contacts to Nextcloud

he first thing you must do is log into your Nextcloud account. Go to the Contacts app and, in the bottom left corner, click on the Settings gear icon. Click on the menu button (three horizontal dots) and then, from the drop-down menu, click Copy link.

Now head over to Thunderbird and open the Card Book tab. In this window, right-click the left pane and select New Address Book.

In the first window of the wizard select Remote and click Next. In the second window (Figure C), select CardDAV and then paste the URL from Nextcloud in the URL area. Type your Nextcloud credentials below that and click Validate.

Once the validation succeeds, click Next. In the resulting screen, give the Address Book a name, select a color, and then click Next. In the final screen, click Finish, and you’re done.

If the newly created Address Book doesn’t immediately sync, click the Synchronize button, and you’re good to go.

Hezkuntzan ere Librezale

Hezkuntzan ere Librezale fue creado en 2017 por padres, profesores, alumos y agentes de Euskal Herria, preocupados por la creciente presencia de grandes empresas privadas en los procesos de digitalización de nuestras escuelas.

Según hemos sabido, el Gobierno Vasco pondrá a disposición de Google y Microsoft las identidades digitales de miles de estudiantes vascos. La situación es similar en otros ámbitos de la educación, como Navarra, Iparralde o la asociación de ikastolas. Por otro lado, el despliegue de dispositivos Chromebook en los centros educativos es cada vez más amplio, a menudo impulsado por las propias instituciones.

Colectic. Tecnologia per la transformació social

Colectic és un projecte cooperatiu sense ànim de lucre que treballa per la inclusió, l’autonomia i l’apoderament de les persones i les comunitats als àmbits social, laboral i tecnològic; tot entenent i utilitzant la tecnologia com una eina de participació i transformació social.

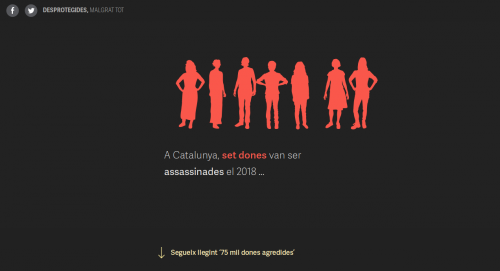

Desprotegides, Malgrat tot

La violència contra les dones és un problema estructural, d’enorme complexitat. A Catalunya, una de cada quatre dones ha patit algun cas greu de violència masclista al llarg de la seva vida. Ni el perfil dels agressors ni el de les víctimes es pot associar a una classe social, estudis, edat o situació econòmica. Elles se senten desprotegides pel sistema perquè veuen com es posa en dubte o es minimitza la violència masclista viscuda quan l’expliquen als jutges. S’han creat protocols d’atenció i nombrosos serveis per acompanyar-les, però no n’hi ha prou. Són eficients les polítiques públiques dedicades a erradicar la violència masclista? I el pressupost que s’hi inverteix?

Data Feminism book review

We have chosen to put this draft online because of a foundational principle of this project: that all knowledge is incomplete, and that the best knowledge is gained by bringing together multiple partial perspectives. A corollary to this principle is that our own perspectives are limited, especially with respect to the topics and issues that we have not personally experienced.

REISUB – the gentle Linux restart

Holding down Alt and SysRq (which is the Print Screen key) while slowly typing REISUB will get you safely restarted. REISUO will do a shutdown rather than a restart.

Sounds like either an April Fools joke or some very strange magic akin to the old BIOS beeps we used to use to diagnose PC faults so bad that nothing would boot. Wikipedia comes to the rescue with an in-depth listing of all the SysRq keys.

R: Switch the keyboard from raw mode to XLATE mode

E: Send the SIGTERM signal to all processes except init

I: Send the SIGKILL signal to all processes except init

S: Sync all mounted filesystems

U: Remount all mounted filesystems in read-only mode

B: Immediately reboot the system, without unmounting partitions or syncing

How Many Satellites are Orbiting the Earth?

Satellites are tracked by United States Space Surveillance Network (SSN), which has been tracking every object in orbit over 10 cm (3.937 inches) in diameter since it was founded in 1957. There are approximately 3,000 satellites operating in Earth orbit, according to the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), out of roughly 8,000 man-made objects in total. In its entire history, the SSN has tracked more than 24,500 space objects orbiting Earth. The majority of these have fallen into unstable orbits and incinerated during reentry. The SSN also keeps track which piece of space junk belongs to which country.

How to manage a 30-person housing cooperative

…decentralized working circles that (mostly) have free association with one another

All circles are open for any housemate to join, and everyone must be a part of at least one circle. However, looking closer at circle operations reveal different degrees of centralized decision-making and chain communication. For example, all circles have rotating “lead” position, some of which are paid. The lead circle is responsible for facilitating that circle’s tasks alongside acting as the circle’s primary representative with the larger community.

Integrating all three network styles allows us to successfully maneuver the tension between having an organized framework to maintain a cohesive, happy household and one that is dynamic and open to changing needs of our housemates. However, to make this function smoothly requires buy-in from all members. We aim to reaffirm our commitment at our bi-monthly, all-house meetings, where the circles report on their progress to the entire community. We find that this is usually when most conflict arises — but we work together to address triggers and fill in gaps in our structure. Doing this ensures that we’re all taking responsibility for each other’s well-being and creating experiences that wouldn’t be possible if we went at it alone.

Print the whole webpage in a single image file

It only does PNG, but Firefox has a way to capture the whole page built in: Shift-F2 brings up a command prompt, which includes a screenshot command. For instance, screenshot –clipboard –fullpage as I was writing this answer produced http://imgur.com/tnplKPE.

If you want something designed to be automated, phantomjs has page.render() which takes a filename and an optional options object, with format and quality entries; the example given is

page.render('google_home.jpeg', {format: 'jpeg', quality: '100'});

Professionnels, ne pas fermer votre Wi-Fi pourrait vous coûter cher

Jeudi, nous rapportions qu’avec sa décision Tobias Mc Fadden prise pour une affaire de piratage de fichiers MP3, la Cour de justice de l’Union européenne (CJUE) a véritablement condamné à mort les réseaux Wi-Fi ouverts, en exigeant que les professionnels qui offrent un tel service recueillent l’identité des internautes qui s’y connectent, et conservent un journal de leurs connexions. Ceux qui ne le font pas s’exposeront à des conséquences financières, alors-même que la Cour estime qu’ils ne sont pas responsables des téléchargements illégaux effectués avec leur connexion.

La CJUE met à mort le Wi-Fi public anonyme, au nom du droit d’auteur

La Cour était interrogée par la justice allemande au sujet d’un gestionnaire d’une boutique de sons et lumières, qui proposait un accès Wi-Fi gratuit et ouvert à tous ses clients, sans le sécuriser contre le téléchargement sur les réseaux Peer-to-Peer (P2P). Sony Music demandait que le commerçant soit tenu civilement responsable des téléchargements illégaux de fichiers MP3 réalisés par des tiers à travers cette connexion, et qu’il lui soit fait obligation de sécuriser le réseau Wi-Fi.

WordPress Function Reference: media sideload image

Download an image from the specified URL and attach it to a post.

media_sideload_image($file, $post_id, $desc, $return);

Transforming our communities through media-based organizing

The Allied Media Conference emerges out of 20 years of relationship-building across issues, identities, organizing practices and creative mediums. Since the first conference (then the Midwest Zine Conference) in 1999, people have been compelled by the concept of do-it-yourself media. The zine conference was rebranded as the “Underground Publishing Conference” for a couple years and then became the Allied Media Conference in 2002. The shift to Allied Media attracted more people who were interested in using participatory media as a strategy for social justice organizing.

Python’s re Module

Python is a high level open source scripting language. Python’s built-in “re” module provides excellent support for regular expressions, with a modern and complete regex flavor. The only significant features missing from Python’s regex syntax are atomic grouping, possessive quantifiers, and Unicode properties.

The first thing to do is to import the regexp module into your script with import re.

HTTP download file with Python

The urllib2 module can be used to download data from the web (network resource access). This data can be a file, a website or whatever you want Python to download. The module supports HTTP, HTTPS, FTP and several other protocols.

How to Check if a File Exists in Python: Try/Except, Path, and IsFile

If we’re looking to check if a file exists, there are a few solutions:

Check if a file exists with a try/except block (Python 2+)

Check if a file exists using os.path (Python 2+)

Check if a file exists using the Path object (Python 3.4+)

Turnometro

A web tool for more effective & inclusive assemblies.

Get all languages cpt posts on frontend. Search query

I suggest that you use $query->set( ‘lang’, ” ); in a function hooked to parse_query with priority 1.

Hoy empieza todo con Marta Echeverría – Con Laura Freixas

Hablamos de feminismo, maternidad y contradicciones con Laura Freixas, que nos presenta A mí no me iba a pasar, una autobiografía en la que repasa su vida entre 1985 y 2003.

A method for giving credit to organizations that contribute code to Open Source

Open Source projects would benefit from this level of transparency and that giving credit directly into the commit message makes it very transferable.

With this level of transparency, we can start to study how our ecosystem actually works; we can see which companies contribute back code and how much, we can see how much of the Drupal project is volunteer driven, we can better identify potential conflicts of interest, and more. But most of all, we can provide credit where credit is due and provide meaningful incentives for organizations to contribute back to Drupal. I believe this could provide a really important step in making Drupal core development more scalable.

William Klein. Manifiesto

William Klein (Nueva York, 1928) revolucionó la historia de la fotografía, estableciendo las bases de una estética moderna que todavía pervive: una estética en contacto directo con una sociedad de posguerra aun por reconstruir, imaginar, soñar.

Los múltiples rostros reflejados en las obras narran la historia de una humanidad cosmopolita, ruidosa, alegre, vivida y observada por un hombre que se regocija sin descanso en su embriagador movimiento.

Hay algo que recorre la obra de William Klein: la línea, que conecta y estructura, que brota y corre.Geometría urbana y geometría humana. La estética de William Klein nos habla de un siglo en movimiento, un siglo de cambios, creaciones y revoluciones. Siempre ubicado en el centro, cerca del foco para captar mejor las líneas de tensión, construyó durante una década (la de 1950) estos grandes conjuntos en el corazón de Nueva York, luego en Roma, Moscú y Tokio, que hoy son monumentos de la historia de la fotografía.

La commune est à nous !

Un enseignement en ligne gratuit sur le municipalisme.

« La commune est à nous ! », accessible en ligne, répond à vos questions en 8 étapes pour comprendre la radicalité démocratique et construire une nouvelle éthique politique. Quelles sont les clés pour ouvrir collectivement les portes d’une municipalité ? Quelles expériences existent déjà, quels sont leurs succès, leurs difficultés ? Quelles méthodes utiliser pour inclure les habitants ? Comment animer une assemblée citoyenne et parvenir à une décision portée par tous ?

Who Will Win the Twenty-First Century?

Yet in the twenty-first century, power will be determined not by one’s nuclear arsenal, but by a wider spectrum of technological capabilities based on digitization. Those who aren’t at the forefront of artificial intelligence (AI) and Big Data will inexorably become dependent on, and ultimately controlled by, other powers. Data and technological sovereignty, not nuclear warheads, will determine the global distribution of power and wealth in this century. And in open societies, the same factors will also decide the future of democracy.

The most important issue facing the new European Commission, then, is Europe’s lack of digital sovereignty. Europe’s command of AI, Big Data, and related technologies will determine its overall competitiveness in the twenty-first century. But Europeans must decide who will own the data needed to achieve digital sovereignty, and what conditions should govern its collection and use.

La administración no libera el código libre ni para datos abiertos

Pese a tanta recomendación y que sea software libre, cuando pides el código fuente de esta plataforma, la respuesta de red.es argumenta que su liberación podría ocasionar un perjuicio para su poseedores (red.es como reconocen en la resolución) y se acogen a esta cláusula de la ley de transparencia acceso a la información y buen gobierno para denegarlo. (Pese a que dicen que conceden parcialmente, la realidad es que no conceden nada)

La historia detrás de un estadio llamado Cantona

Conocido es también su apoyo a la Fundación Abbé Pierre para la construcción de viviendas sociales y la limitación del precio de los alquileres, pues a su juicio es “inaceptable que haya gente hoy que tiene que hacer enormes sacrificios con la educación de sus hijos, a veces incluso con su salud, para tener un alojamiento”.

cuando Eric tenía 30 años, decidió retirarse del fútbol. “He sido profesional durante 13 años, es demasiado tiempo. Me gustaría hacer otras cosas en mi vida”

This Article Is Spying on You

Surveillance on news websites is particularly problematic because the news you consume may reveal your political leanings or health interests — information that is not just exploited by corporations to sell you things, but could also be abused by governments. And because news organizations benefit from the surveillance economy by running advertisements targeted to reader interests, they may be less likely to report on their own tracking practices.

The Times’s privacy policy does not disclose the vast majority of tracking companies (including BlueKai) on its site, requires users to accept cookies to fully use the site and explicitly states that The Times ignores the “do not track” browser setting.

Worse, only 10 percent of these outside parties are disclosed in privacy policies of the news sites we studied, meaning even diligent readers will never learn who collects their data. From a privacy perspective, news websites are among the worst on the web.

The result is that as online advertising networks become more highly centralized, the old model of a independently managed and free press is being replaced by one where giant technology companies control user data and the purse strings.

Webxray. Find third party trackers with privacy forensics

Users are tracked online by a multitude of companies in order to build detailed records of individual browsing behaviors, often without consent. Many website operators are unaware of the user data they collect, and more importantly, the third parties who collect data on visitors to their sites.

Identifying data leaks and locating inadequate privacy policies which govern this type of data collection is critical in the context of new international regulations governing data protection.

Balancing Makers and Takers to scale and sustain Open Source

This blog post talks about how we can make it easier to scale and sustain Open Source projects, Open Source companies and Open Source ecosystems.

How do you get others to contribute? How do you get funding for Open Source work? But also, how do you protect against others monetizing your Open Source work without contributing back? And what do you think of MongoDB, Cockroach Labs or Elastic changing their license away from Open Source?

Top of mind is the need for Open Source projects to become more diverse and inclusive of underrepresented groups.

The difference between Makers and Takers is not always 100% clear, but as a rule of thumb, Makers directly invest in growing both their business and the Open Source project. Takers are solely focused on growing their business and let others take care of the Open Source project they rely on.

Organizations can be both Takers and Makers at the same time. For example, Acquia, my company, is a Maker of Drupal, but a Taker of Varnish Cache. We use Varnish Cache extensively but we don’t contribute to its development.

I’ve long believed that Open Source projects are public goods: everyone can use Open Source software (non-excludable) and someone using an Open Source project doesn’t prevent someone else from using it (non-rivalrous).

However, through the lens of Open Source companies, Open Source projects are also common goods; everyone can use Open Source software (non-excludable), but when an Open Source end user becomes a customer of Company A, that same end user is unlikely to become a customer of Company B (rivalrous).

Interestingly, all successfully managed commons studied by Ostrom switched at some point from open access to closed access.

the shared resource must be made exclusive (to some degree) in order to incentivize members to manage it. Put differently, Takers will be Takers until they have an incentive to become Makers.

Once access is closed, explicit rules need to be established to determine how resources are shared, who is responsible for maintenance, and how self-serving behaviors are suppressed. In all successfully managed commons, the regulations specify (1) who has access to the resource, (2) how the resource is shared, (3) how maintenance responsibilities are shared, (4) who inspects that rules are followed, (5) what fines are levied against anyone who breaks the rules, (6) how conflicts are resolved and (7) a process for collectively evolving these rules.

Mozilla has the exclusive right to use the Firefox trademark and to set up paid search deals with search engines like Google, Yandex and Baidu. In 2017 alone, Mozilla made $542 million from searches conducted using Firefox. As a result, Mozilla can make continued engineering investments in Firefox. Millions of people and organizations benefit from that every day.

One way to implement this is Drupal’s credit system. Drupal’s non-profit organization, the Drupal Association monitors who contributes what. Each contribution earns you credits and the credits are used to provide visibility to Makers. The more you contribute, the more visibility you get on Drupal.org (visited by 2 million people each month) or at Drupal conferences (called DrupalCons, visited by thousands of people each year).

It can be difficult to understand the consequences of our own actions within Open Source. Open Source communities should help others understand where contribution is needed, what the impact of not contributing is, and why certain behaviors are not fair. Some organizations will resist unfair outcomes and behave more cooperatively if they understand the impact of their behaviors and the fairness of certain outcomes.

look at what MariaDB did with their Business Source License (BSL). The BSL gives users complete access to the source code so users can modify, distribute and enhance it. Only when you use more than x of the software do you have to pay for a license. Furthermore, the BSL guarantees that the software becomes Open Source over time; after y years, the license automatically converts from BSL to General Public License (GPL), for example.

Un servidor con GNU/Linux, posiblemente el único que sigue funcionando en el Ayuntamiento de Jerez tras el ciberataque

El ciberataque al Ayuntamiento de Jerez ha dejado sin prácticamente ningún servicio informático a todo el ayuntamiento, sin embargo, posiblemente el único servidor importante con GNU/Linux en el Ayuntamiento de Jerez sigue funcionando, permitiendo que los distintos departamentos al menos no estén incomunicados.

Curso de Introducción a R

Creemos que al final seréis capaces de utilizar R para cargar datos, arreglarlos, hacer gráficos y tablas, e informes en Rmarkdown.

Intentaremos que el curso sea fundamentalmente práctico, perso se necesita un mínimo de conocimiento sobre el funcionamiento de determinadas cosas y también hay que conocer un poco la jerga que se utiliza en la comunidad R.

En lugar de presentar todos los pormenores de R de manera lineal, se irán presentando distintos aspectos de R conforme se vayan necesitando; es decir, no vamos a presentar R como un lenguaje de programación sino como una herramienta para hacer análisis estadísticos.

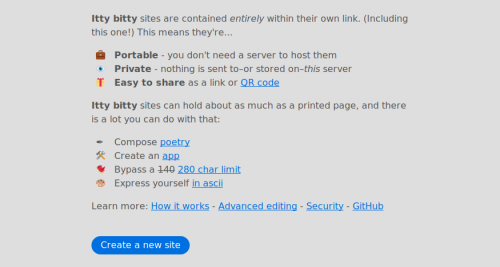

How itty.bitty works

TL;DR:

itty.bitty takes html (or other data), compresses it into a URL fragment, and provides a link that can be shared. When it is opened, it inflates that data on the receiver’s side.

This amazing new web tool lets you create microsites that exist solely as URLs

…self-contained microsites that exist solely as URLs

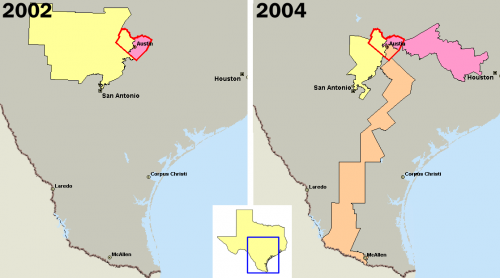

Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering is a practice intended to establish a political advantage for a particular party or group by manipulating district boundaries.

Creative Commons Image Search

Search for free content in the public domain and under Creative Commons licenses.

PHP Compatibility Checker

The WP Engine PHP Compatibility Checker can be used by any WordPress website on any web host to check PHP version compatibility.

Rosalía o el gran pecado español: por qué muchos no soportan su éxito

Rosalía trabajó 18 meses componiendo, produciendo y arreglando El mal querer de forma independiente y solo después de la repercusión de Malamente y Pienso en tú mirá (ambos videoclips financiados por ella) la multinacional discográfica Sony le ofreció un contrato.

Nadie ha atacado a Antonio Banderas, Óscar Jaenada o Jordi Mollà por trabajar en Estados Unidos como sí se ha ridiculizado a Penélope Cruz, Elsa Pataki o Paz Vega por hacer exactamente lo mismo. De Fernando Rey se aplaude que saliese en French Connection, de Sara Montiel se recuerda cómo le freía huevos con ajo a Marlon Brando.

La clase social de los hermanos Muñoz de Estopa fue uno de los baluartes de su éxito y no se les calificó, como ocurre con Rosalía, de “choni poligonera” o “cani de extrarradio”.

Homeopatía y antivacunas: así ponen algunas personas en peligro a sus mascotas

Existen algunos estudios científicos destinados a comprobarlo y la mayoría concluyen lo mismo: que la recuperación visible de los síntomas del animal depende de la percepción de los mismos de sus propietarios o el veterinario que le ha recetado la homeopatía, de modo que de nuevo hay un cerebro humano en el que puede estar calando el efecto placebo. En resumen, lo más probable es que un perro que ha tomado homeopatía siga igual de enfermo después, pero puede ocurrir que su dueño sí crea ver que los síntomas mejoran.

Así se expande la desinformación sanitaria por Internet y redes sociales

un estudio realizado en Facebook detectó que, de los 10 artículos más compartidos en esta red, 7 de ellos eran engañosos o contenían alguna información falsa. Además, en 2016, más de la mitad de los 20 artículos más compartidos con “cáncer” en sus titulares fueron desacreditados por médicos y autoridades sanitarias.

Los bulos más predominantes a los que se enfrentaban los médicos tenían que ver con las pseudoterapias, la alimentación, el cáncer y efectos secundarios de medicamentos. Sin embargo, la variedad de la desinformación sanitaria que se transmite por Internet es enorme: pollos a los que les administran hormonas para que crezcan, desodorantes y antitranspirantes que provocan cáncer de mama, un hospital que afirma que la quimioterapia es “la gran equivocación médica”, el limón como cura del cáncer, plátanos infectados de SIDA…

La información sanitaria errónea siempre ha estado presente en las sociedades humanas, no es algo nuevo. No obstante, las nuevas tecnologías han cambiado las reglas del juego, por así decirlo. Los bulos de salud se expanden como nunca antes por las redes sociales gracias a su capacidad para llegar a miles o millones de personas en minutos u horas. Estas redes son amplificadores bestiales de la desinformación porque la desinformación suele presentarse de forma atractiva para el internauta. Los bulos más populares tienen contenidos claros, impactantes, llamativos o atractivos. También cuidan mucho la presentación y suelen ser muy visuales. Su rasgo más poderoso es despertar emociones en la audiencia, ya sea miedo, esperanza, sorpresa, curiosidad, indignación… Se sabe que las noticias se difunden mucho más cuando éstas despiertan reacciones emocionales porque nos sentimos más involucrados.

Además de las redes sociales, los buscadores de Internet son otro factor con un gran papel en la difusión de bulos de salud. Los grandes buscadores funcionan de forma automática basándose en unos algoritmos que determinan la posición de las páginas web en los resultados. No hay profesionales activos que filtren las informaciones sanitarias falsas o erróneas, sino que esto queda en manos de las “máquinas”. Esto permite la visibilidad y difusión de ciertos contenidos en Internet que no llegarían muy lejos si existieran humanos vigilando.

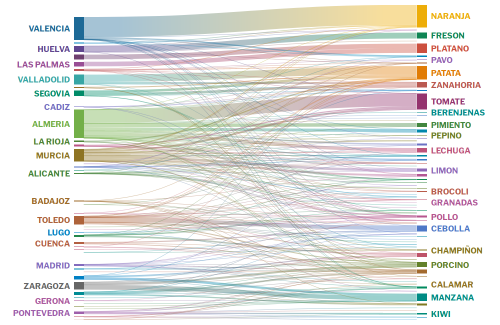

¿Qué comemos en Madrid, y de donde viene?

Una exploración sobre los alimentos que pasan por Mercamadrid

ECO. Música y Comunidad en Residencias de Mayores

Esta es una de las premisas de ECO. Transformar la lógica de los cuidados en los Centros de Mayores hacia una apuesta fuerte por fortalecer sus lazos interpersonales.

De esta forma, ECO trabaja desde la creación de redes de apoyo comunitarias en el centro, usando la música, los recuerdos y las vivencias de los participantes como herramientas principales.

Esta serendipia nos pasa bastante a menudo en Panic. Lo que llamamos: “hacer visible lo invisible”

Cantantes, músicas, amantes del baile… Los talentos ocultos empezaron a florecer:

“Cómo puede ser que llevemos tanto tiempo aquí y no conociera esta parte de ti?”

Pata Negra: anarquía y flamenco rock

…un programa de Pata Negra dedicado a los hermanos Rafael y Raimundo Amador y a uno de los discos más importantes de la historia del flamenco moderno y el pop español, Blues de la frontera, un disco en la orilla del rock y del flamenco, una obra maestra en la que se ha sumergido el periodista musical Marcos Gendre para escribir: “Blues de la frontera. Anarquía y libertad de los Amador”.

SSD vs. HDD: What’s the Difference?

An SSD does functionally everything a hard drive does, but data is instead stored on interconnected flash-memory chips that retain the data even when there’s no power present. These flash chips are of a different type than the kind used in USB thumb drives, and are typically faster and more reliable.

The PC hard drive form factor standardized at 5.25 inches in the early 1980s, with the now-familiar 3.5-inch desktop-class and 2.5-inch notebook-class drives coming soon thereafter. The internal cable interface has changed from serial to IDE (now frequently called Parallel ATA, or PATA) to SCSI to Serial ATA (SATA)

An SSD-equipped PC will boot in less than a minute, and often in just seconds. A hard drive requires time to speed up to operating specs, and it will continue to be slower than an SSD during normal use.

Because of their rotary recording surfaces, hard drives work best with larger files that are laid down in contiguous blocks. That way, the drive head can start and end its read in one continuous motion. When hard drives start to fill up, bits of large files end up scattered around the disk platter, causing the drive to suffer from what’s called fragmentation. While read/write algorithms have improved to the point that the effect is minimized, hard drives can still become fragmented to the point of affecting performance. SSDs can’t, however, because the lack of a physical read head means data can be stored anywhere without penalty. Thus, SSDs are inherently faster.

An SSD has no moving parts, so it is more likely to keep your data safe in the event you drop your laptop bag or your system gets shaken while it’s operating.

SSDs make no noise at all; they’re non-mechanical.

An SSD doesn’t have to expend electricity spinning up a platter from a standstill. Consequently, none of the energy consumed by the SSD is wasted as friction or noise, rendering them more efficient.

While it is true that SSDs wear out over time (each cell in a flash-memory bank can be written to and erased a limited number of times), thanks to TRIM command technology that dynamically optimizes these read/write cycles, you’re more likely to discard the system for obsolescence (after six years or so) before you start running into read/write errors with an SSD.

¿Qué es un centro social?

Un centro social es una institución anómala. Funciona de acuerdo con lógicas a las que no estamos acostumbrados. La vida de un centro social viene regulada por los propios participantes en el mismo, sin mediación de la administración y tampoco de empresas comerciales. La responsabilidad es colectiva, la actividad es colectiva, la administración es colectiva.

Su éxito radicaba en que no hacía falta más que interés e iniciativa para usar estos espacios.

Sólo en la región de Madrid existen unos 60 espacios de este tipo.

En España hay más de 600 centros sociales.

En muchas ciudades alemanas e italianas los centros sociales son realidades tan corrientes que las instituciones los han acabado por reconocer, los han dejado de molestar.

Pocas ciudades han sido tan inteligentes, en este sentido, como la ciudad de Nápoles. Allí, la alcaldía, a instancias de la mayor parte de los movimientos sociales de la ciudad, ha establecido un estatuto particular para los centros sociales. Los espacios napolitanos han sido declarados comunes urbanos. Esto quiere decir, sencillamente, que el ayuntamiento los considera entidades legítimas; y a su vez entidades que no son de su competencia.

Un centro social es así un comunal urbano, un espacio sobre el que una parte de la ciudadanía decide tomar posesión, gestionarlo directamente y generar una riqueza que ni el mercado ni ninguna burocracia serían capaces jamás de producir.